You Won’t Believe These Hidden Architectural Gems in Apia, Samoa

When I stepped into Apia, I expected palm trees and beaches—but not the stunning architecture hiding in plain sight. From colonial-era churches to traditional fale designs, the city’s buildings tell stories of culture, resilience, and quiet beauty. Most travelers miss this side of Samoa, yet it’s one of the most authentic ways to understand the islands. Let me take you where the guidebooks don’t.

First Impressions: Apia’s Unexpected Urban Landscape

Apia, the capital of Samoa, unfolds not with the grandeur of a bustling metropolis but with the gentle rhythm of a Pacific town shaped by history, nature, and community. To the untrained eye, its streets may appear modest—low-rise buildings, open-air markets, and roads that meander rather than race. Yet beneath this simplicity lies a rich architectural narrative that reflects centuries of cultural exchange, adaptation, and identity. Unlike typical tropical destinations celebrated solely for their beaches, Apia offers a more nuanced experience: a living museum of design where every structure, from the smallest village meeting house to the stately Centenary Methodist Church, speaks to the values and history of the Samoan people.

What makes Apia’s urban landscape so compelling is its refusal to conform to expectations. There are no glass towers or sprawling shopping malls. Instead, the city’s character emerges through its thoughtful use of space, natural materials, and climate-responsive design. Buildings are often raised off the ground, constructed with wide eaves and open sides to invite cooling breezes—a practical response to the humid tropical climate that also reflects a cultural preference for openness and connection. This architectural philosophy prioritizes harmony over dominance, blending human habitation with the surrounding environment in a way that feels both intentional and deeply rooted.

Architecture in Apia is not merely about shelter; it is a lens through which to understand Samoan society. The layout of homes, the orientation of churches, and the design of public spaces all reflect communal values, social hierarchy, and spiritual beliefs. For instance, the placement of a fale—the traditional Samoan house—within a family compound follows strict cultural protocols that emphasize respect, lineage, and collective living. By observing these details, visitors gain insight into a way of life that values balance, respect, and continuity. In a world where globalized design often erases local identity, Apia stands as a quiet testament to the power of place-based architecture.

The Legacy of Colonial Design: German and Missionary Influences

The architectural fabric of Apia bears the subtle imprint of 19th-century colonial powers, particularly Germany and the British missionary societies that played a significant role in shaping the islands’ built environment. While Samoa was never subjected to large-scale colonial urban planning, the presence of European settlers introduced new materials, construction techniques, and aesthetic sensibilities that merged with local traditions to create a distinctive hybrid style. Today, remnants of this era can still be found in the quiet neighborhoods of Mulinu’u and Vailima, where weathered wooden homes with corrugated iron roofs stand as quiet witnesses to a complex past.

German influence in Apia’s architecture is most evident in the administrative buildings and private residences constructed during the late 1800s. These structures often feature symmetrical facades, tall shuttered windows, and verandas supported by timber columns—design elements adapted from European models but modified to suit the tropical climate. The use of corrugated iron, imported from Europe, became widespread due to its durability and resistance to heavy rainfall. Similarly, timber framing allowed for ventilation and flexibility in construction, making it ideal for a region prone to cyclones. Over time, these materials were embraced not as foreign impositions but as practical solutions that complemented Samoan building practices.

Missionaries, particularly from the London Missionary Society, also left a lasting architectural legacy. Their homes and schools were designed to be functional and modest, reflecting their religious values while accommodating local conditions. Many of these buildings incorporated raised floors, steeply pitched roofs, and wide overhangs—features that would later influence both church and domestic architecture. What is remarkable is how these imported designs were not imposed wholesale but were instead adapted to align with Samoan customs. For example, the open layout of missionary homes mirrored the openness of the fale, facilitating social interaction and communal living.

Today, preservation efforts are helping to safeguard these historic structures. While some colonial-era buildings have been lost to time or redevelopment, others have been restored with care, recognizing their value as cultural artifacts. These buildings do not glorify colonialism but rather serve as honest records of a shared history—one marked by both conflict and collaboration. Their quiet dignity invites reflection on how cultures can influence one another without erasing identity. For the discerning traveler, walking through these neighborhoods offers a rare opportunity to see how Apia’s past continues to shape its present, one timber beam and iron roof at a time.

Sacred Spaces: Churches That Define the Skyline

No visit to Apia is complete without encountering its churches—imposing yet graceful structures that rise above the treetops like beacons of faith and community. Among the most iconic is the Centenary Methodist Church, a grand wooden building with a towering steeple and expansive open sides that allow sea breezes to flow freely through its sanctuary. Nearby, the Sacred Heart Cathedral stands as a testament to Catholic presence in Samoa, its arched windows and bell tower blending European ecclesiastical design with Pacific functionality. These sacred spaces are not just places of worship; they are architectural expressions of how Samoan culture has absorbed and reinterpreted foreign traditions.

What distinguishes Apia’s churches is their thoughtful adaptation to the local environment and social customs. Unlike enclosed European cathedrals, many Samoan churches are built with open or semi-open walls, allowing for natural ventilation in the humid climate. Their steeply pitched roofs, often covered in corrugated metal, are designed to shed heavy tropical rains efficiently. Raised platforms elevate the main floor, protecting against flooding and reinforcing a sense of reverence—visitors must step up to enter, symbolizing a transition from the everyday to the sacred. These design choices reflect a deep understanding of both practical needs and spiritual symbolism.

Equally significant is the way these churches embody Samoan communal values. In traditional society, the matai (chiefly system) governs decision-making, and this hierarchy is mirrored in church seating arrangements, where families and village leaders occupy designated spaces. The open interior encourages collective participation, reinforcing the idea that worship is a shared experience. Even the bell towers, though inspired by European models, are scaled to fit the island context—modest in height but resonant in sound, calling communities together across distances. These churches are not isolated religious edifices; they are central to village life, hosting weddings, funerals, meetings, and celebrations.

For visitors, stepping into one of Apia’s churches is an invitation to witness living tradition. The scent of polished wood, the sound of hymns sung in Samoan, and the sight of congregants dressed in fine ie faitaga (traditional attire) create a multisensory experience that transcends architecture. These buildings are not relics of the past but vibrant centers of cultural continuity. They remind us that faith, like design, is shaped by place—and in Samoa, it is expressed with both reverence and resilience.

Fale and Traditional Samoan Architecture

At the heart of Samoan architectural identity lies the fale, a structure so simple in form yet so profound in meaning that it serves as a blueprint for understanding the culture itself. Traditionally circular or oval in shape, the fale consists of wooden posts supporting a domed roof made of woven thatch, with no permanent walls. This open design is not a limitation but a deliberate choice—one that fosters connection, transparency, and a deep relationship with nature. Whether used as a family home, a meeting house, or a ceremonial space, the fale embodies the Samoan values of hospitality, community, and harmony with the environment.

The construction of a fale is a communal effort, guided by ancestral knowledge passed down through generations. Skilled craftsmen, known as tufuga fau fale, oversee the process, ensuring that proportions, materials, and orientation adhere to cultural standards. The number of wooden posts, for example, often corresponds to family rank or social status, with higher-ranking families having more posts in their chief’s house. The thatched roof, typically made from sugarcane leaves or palm fronds, is carefully layered to provide insulation and waterproofing, demonstrating an intimate understanding of local materials and climate.

One of the most striking aspects of the fale is its spatial organization. Inside, seating follows a strict protocol based on social hierarchy. The head of the family or village chief sits at the back, furthest from the entrance, while guests are seated to the sides. This arrangement reinforces respect and order, turning the physical space into a stage for cultural performance. Even the act of entering the fale carries meaning—visitors remove their shoes and approach with humility, acknowledging the sanctity of the space.

While modern housing in Apia often uses concrete and glass, the influence of the fale remains strong. Government buildings, cultural centers, and even airport terminals incorporate fale-inspired designs, using curved roofs, open layouts, and natural materials to honor tradition. These adaptations demonstrate that heritage need not be frozen in time; it can evolve while retaining its essence. For the traveler, seeing a modern interpretation of the fale offers a powerful reminder that Samoa’s culture is not a relic but a living, breathing presence in everyday life.

Modern Apia: Blending Old and New

As Apia grows, its architectural landscape faces the delicate challenge of balancing progress with preservation. New government offices, schools, and commercial buildings are rising to meet the needs of a developing capital, yet many of these structures draw inspiration from traditional Samoan design. This fusion of old and new is evident in the Faletele at the National University of Samoa, where a large, open-air meeting hall mimics the form of a traditional fale but uses reinforced concrete and modern roofing materials for durability. Similarly, the Samoa Conservation Society’s visitor center features wide eaves, natural ventilation, and locally sourced timber, proving that sustainability and cultural identity can go hand in hand.

However, not all modern construction in Apia respects its architectural heritage. Some imported designs—boxy concrete buildings with small windows and minimal shading—ignore the lessons of climate-responsive architecture, leading to uncomfortable indoor environments and higher energy costs. These structures stand in stark contrast to the thoughtful design of older buildings, which evolved in response to real environmental and social needs. The challenge for urban planners is to promote building codes and design guidelines that encourage climate-smart, culturally appropriate architecture without stifling innovation.

One promising trend is the increasing use of green building principles in public projects. Rainwater harvesting, solar panels, and passive cooling techniques are being integrated into new constructions, reflecting a broader awareness of environmental sustainability. At the same time, architects are collaborating with local communities to ensure that designs reflect Samoan values and aesthetics. This participatory approach helps prevent cultural erasure and fosters a sense of ownership among residents.

For visitors, the contrast between old and new offers a compelling narrative about resilience and adaptation. Apia is not a static museum piece; it is a living city navigating the complexities of modernization while holding fast to its roots. By observing how tradition informs contemporary design, travelers gain a deeper appreciation for the ingenuity and wisdom embedded in Samoan architecture. It is a reminder that progress need not come at the expense of identity—that the future can be built on the foundation of the past.

Hidden Spots: Off-the-Beaten-Path Architectural Finds

Beyond the main roads and tourist sites, Apia harbors quiet corners where time seems to slow and history whispers from weathered timbers and shaded verandas. In the neighborhood of Vailima, once home to Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson, a cluster of restored plantation houses offers a glimpse into Samoa’s colonial-era domestic life. Though Stevenson’s former residence is the most famous, lesser-known homes nearby showcase the same blend of European design and tropical adaptation—wide porches, high ceilings, and louvered windows that catch every breeze. These homes, now maintained by local families or cultural organizations, stand as quiet testaments to a layered past.

Another hidden gem lies in the village of Leulumoega, just a short drive from the city center, where community halls known as fale tele showcase exquisite woodcarving and traditional craftsmanship. These large meeting houses, used for village councils and ceremonies, feature intricately carved posts and ornate ceiling beams that tell ancestral stories through symbolic patterns. Unlike tourist-oriented replicas, these structures are actively used, preserving both their function and their cultural significance. Visiting them requires permission and respect, but the experience is deeply rewarding—a chance to witness architecture not as a static display but as a living tradition.

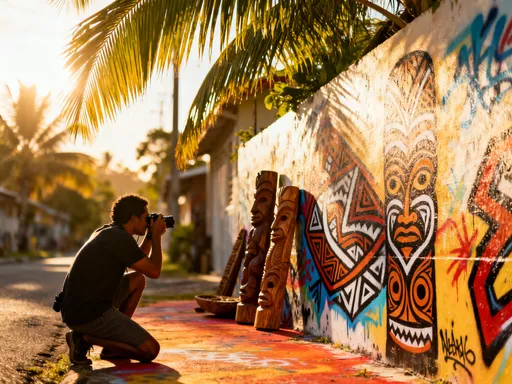

For those who prefer to explore on foot, a self-guided walking tour through Apia’s older districts can yield unexpected discoveries. Along Beach Road and parts of Malo Street, 19th-century administrative buildings with timber frames and corrugated roofs still stand, their facades softened by time and tropical vines. Some have been repurposed as small shops or offices, blending seamlessly into daily life. These quiet survivals remind us that heritage is not always grand or monumental—it can be found in the ordinary, the overlooked, the everyday.

Exploring these hidden spots requires a mindset of respect and curiosity. These spaces are not theme park attractions but parts of living communities. Travelers are encouraged to tread lightly, ask permission when entering private or sacred areas, and support local conservation efforts when possible. By doing so, they contribute to the preservation of Apia’s architectural soul—one respectful visit at a time.

Why This Matters: Architecture as Cultural Memory

The buildings of Apia are more than bricks, timber, and thatch—they are vessels of memory, resilience, and identity. Each structure, whether a centuries-old church, a humble fale, or a modern government building inspired by tradition, carries stories of adaptation, faith, and community. In a world increasingly dominated by homogenized urban design, Apia offers a powerful alternative: a city where architecture reflects not just function, but meaning. To walk through its streets is to engage with a culture that values continuity, respect, and harmony with nature.

Preserving this architectural heritage is not merely about saving old buildings; it is about safeguarding a way of life. When a fale is rebuilt using ancestral methods, when a colonial home is restored with care, when a new public building echoes the form of a traditional meeting house, Samoan identity is reaffirmed. These acts of preservation are quiet acts of resistance against cultural erosion, ensuring that future generations can still read the stories written in wood and stone.

For travelers, looking beyond the beaches and postcard views to see Apia through its architecture is an act of deeper engagement. It invites curiosity, respect, and connection. It transforms a visit from a passive experience into a meaningful encounter with a living culture. So the next time you find yourself in Samoa, take a moment to look up, to step inside, to listen to what the buildings have to say. You may be surprised by what you discover—not just in the structures themselves, but in the values they represent and the stories they quietly tell.