Frame the Soul: Where Vanuatu’s Port Vila Meets Light and Art

You know what? I never expected to find such raw creative energy in Port Vila, Vanuatu. It wasn’t the beaches or resorts that stole my breath—it was the art spaces glowing under tropical light, each one a pulse of culture and color. Through my lens, I discovered something deeper: a city where photography isn’t just about snapping shots, but capturing stories carved in wood, painted on walls, and danced into being. This is more than travel—it’s visual poetry. In a world where destinations often blur into sameness, Port Vila stands apart, not for grand monuments or luxury labels, but for its quiet, persistent creativity. Here, art is not displayed behind velvet ropes. It lives in the hands of carvers, the rhythm of weavers, and the murals that breathe color into concrete. For photographers seeking authenticity, this capital offers a rare gift: the chance to witness culture in motion, shaped by light, land, and legacy.

The First Glimpse: Arriving in Port Vila with a Photographer’s Eye

Touching down at Bauerfield International Airport, the first thing a photographer notices is the light. It’s not the harsh, flat brightness common in many tropical zones, but a soft, golden wash that spills across the tarmac and stretches down the palm-lined road into town. The late afternoon sun filters through coconut fronds, casting long, dappled shadows that dance on corrugated iron roofs and painted wooden shutters. This is not a city of towering skylines or bustling traffic. Instead, Port Vila unfolds slowly, like a well-worn journal opening to reveal its most intimate entries. Its charm lies in the details: the faded pastel hues of colonial-era buildings, the flutter of market fabrics in the breeze, and the quiet hum of life unfolding at a human pace.

For a photographer, this rhythm is a gift. Unlike larger Pacific capitals where urban sprawl blurs the edges of culture, Port Vila maintains a rare balance between accessibility and authenticity. The streets are not cluttered with billboards or commercial chains, but lined with open-air stalls where artisans display hand-carved masks, woven baskets, and painted drums. The air carries the scent of frangipani and woodsmoke, mingling with the salty tang of the nearby sea. Every corner seems to offer a composition waiting to be framed—whether it’s an elderly woman arranging bundles of kava root at the roadside, or a group of children chasing each other past a brightly painted church.

What sets Port Vila apart is its visual texture. The city doesn’t rely on grand gestures to impress. Instead, it invites close looking. The peeling paint on a wooden storefront reveals layers of history. The rust patterns on a metal awning create abstract art shaped by time and rain. Even the shadows cast by woven blinds on a sunlit wall become part of the city’s ever-changing canvas. This is a place where light and materiality conspire to create beauty in the ordinary. For photographers, it’s a reminder that the most compelling images often come not from the spectacular, but from the subtle—the quiet moments between actions, the textures that speak of daily life, and the colors that reflect both land and spirit.

Art Spaces Beyond Galleries: Discovering Creative Hubs in Unexpected Corners

One of the most striking realizations for visitors is that art in Port Vila does not live behind glass or within formal institutions alone. While there are galleries, the true heart of creativity beats in spaces that are communal, informal, and deeply integrated into daily life. A roadside nakamal, traditionally a gathering place for men to drink kava and discuss village matters, might double as an impromptu sculpture workshop where elders guide younger carvers in shaping wooden bowls. A community center in the hills might host weekly tapa cloth-making sessions, where women pound bark into soft sheets and paint them with ancestral symbols. These are not performances for tourists. They are living traditions, unfolding naturally, and they offer photographers unparalleled access to culture in motion.

The Bellevue Art Studio, nestled in a quiet hillside neighborhood, is one such space. Run by a collective of local artists, it functions as both a workshop and a gallery. Here, visitors can watch a carver sand the curves of a grade mask, its spirals and notches representing specific tribal histories. A painter might be mixing natural pigments on a banana leaf, preparing to illustrate a story of sea voyages or spirit encounters. The studio’s open-air design means light floods in from all sides, illuminating the textures of wood, fiber, and paint. For photographers, this is ideal—natural lighting that enhances depth and detail without the flatness of artificial sources. The intimacy of the space allows for close-up shots of hands at work, tools in motion, and the quiet concentration on an artist’s face.

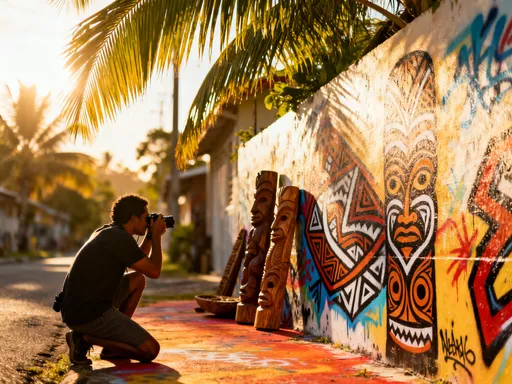

Another vibrant hub is the seafront walkway near the French Cultural Centre, where murals rotate regularly as part of community art projects. These large-scale paintings blend traditional motifs with contemporary themes—spirals that morph into ocean currents, or ancestral faces emerging from storm clouds. The murals are not static. They change with the seasons, often created during festivals or youth workshops. Photographers can capture the process as much as the product: artists on scaffolds, children watching in awe, the paint drying under the tropical sun. These moments tell a broader story about cultural continuity and innovation. They show how art in Port Vila is not preserved like a museum piece, but lived, reshaped, and passed forward.

The Light That Shapes the Image: Timing Your Shoots for Maximum Impact

In Port Vila, light is not just a condition for photography—it is a collaborator. The tropical climate creates dynamic lighting conditions that shift dramatically throughout the day, offering photographers a range of moods and textures to work with. Early morning, just after sunrise, is often the most forgiving. The air is still cool, the humidity lower, and the light soft and diffused. This is the ideal time to photograph the volcanic landscape near Mele Bay, where the low-angle sun gently outlines the contours of the hills and reflects off the calm water. The colors are muted but rich—deep greens, warm browns, and the occasional flash of a bird’s wing catching the light.

By mid-morning, the sun climbs higher, and contrast increases. This can be challenging, but also rewarding for those who know how to use it. Harsh light creates strong shadows, which can be used creatively—think of a weaver sitting in a doorway, half in sunlight, half in shade, her hands illuminated while her face remains in soft darkness. The key is to observe how light interacts with surfaces. Hand-painted signs, often made with bold acrylics on recycled wood, come alive under direct sun. Their colors intensify, and the texture of the paint becomes more pronounced. Similarly, market fabrics—dyed with natural pigments or printed with tribal patterns—glow when backlit, their patterns appearing almost three-dimensional.

The late afternoon, commonly known as the golden hour, is when Port Vila truly transforms. The sun dips toward the horizon, casting a warm, amber glow across the city. This light enhances the natural warmth of wood, the richness of earth tones, and the vibrancy of hand-dyed textiles. It’s the perfect time to photograph outdoor art spaces, where the interplay of light and shadow adds depth and drama to compositions. Overcast days, often following brief afternoon rains, offer another valuable opportunity. The cloud cover acts as a giant softbox, eliminating harsh highlights and creating even illumination. These conditions are ideal for environmental portraits—images that place the subject within their surroundings, showing not just their face, but their world.

Human Stories Through the Lens: Capturing Artists in Action

At the core of Port Vila’s artistic landscape are the people—the makers whose hands carry forward centuries of knowledge. A photograph of a finished mask is striking, but a photograph of the hands shaping it is transformative. These are the images that resonate, that linger in the viewer’s mind. They speak of skill, patience, and cultural pride. To capture them well, however, requires more than technical skill. It demands respect, presence, and a willingness to slow down.

One of the most powerful moments a photographer can witness is a master carver working on a grade mask. These masks are not mere decorations. They represent spiritual beings, ancestral figures, and tribal identities. The process is meticulous—each curve, each notch, carries meaning. To photograph this moment is to document a sacred act. The key is to approach with humility. Always ask for permission, not with a quick gesture, but with eye contact and a few words in Bislama or English. If the artist agrees, wait. Don’t rush to shoot. Let the rhythm of their work guide your timing. The most compelling images often come in the quiet pauses—the moment a carver steps back to assess his work, or the way his fingers trace a completed spiral with quiet satisfaction.

Similarly, photographing women weaving tapa cloth or dyeing fabric with tree bark pigments offers rich storytelling potential. These practices are often passed down through generations, and the act of creation is deeply communal. A group of women might sit together under a thatched roof, laughing as they work, their hands moving in practiced unison. To capture this, use a wide aperture to soften the background and focus on gestures—the clench of a fist around a pestle, the flick of a wrist as dye is applied. Avoid posed shots. Instead, wait for natural moments: a shared glance, a sudden burst of laughter, a hand reaching for a tool. These are the details that convey connection, not just craft.

Blending Tradition and Modernity: The Evolving Aesthetic of Ni-Vanuatu Art

Art in Port Vila is not frozen in time. While deeply rooted in tradition, it is also in constant dialogue with the present. Ni-Vanuatu artists today are reimagining ancestral symbols through contemporary mediums, creating a visual language that honors the past while speaking to the future. This fusion is not a rejection of heritage, but an affirmation of its vitality. It shows that culture is not something to be preserved in amber, but something that grows, adapts, and finds new forms of expression.

One striking example is the reinterpretation of bul motifs—stylized representations of spirits or ancestral beings. Traditionally carved into wood or painted on ceremonial houses, these motifs now appear in acrylic paintings, metal sculptures, and even digital prints. At the Tasiriki Art Village, a collective of young artists uses spray paint and stencils to recreate ancient patterns on concrete walls, transforming urban spaces into open-air galleries. The effect is powerful: the past is not erased, but reasserted in a modern context. For photographers, these juxtapositions offer compelling visual narratives. A smartphone screen displaying a digital sketch of a spirit mask, later carved by hand. A mural of a traditional canoe sailing across a stormy sea, painted on the side of a café. These images tell a story of continuity and resilience.

Another example is the rise of hybrid exhibition spaces like The Hub, a café-gallery that hosts rotating pop-up shows. Here, a teenager might display photographs of village life alongside a grandmother’s hand-woven baskets. The space itself reflects the blending of old and new—concrete floors, exposed beams, and shelves lined with both coffee cups and carved wooden figures. Photographers can capture this duality in a single frame: a young artist adjusting a digital projector while an elder inspects a hand-painted drum. The visual contrast is striking, but the emotional thread is unity—a shared commitment to expression, identity, and community.

Practical Photography Toolkit: Gear, Permissions, and Local Etiquette

While Port Vila offers endless inspiration, photographing here requires thoughtful preparation. The tropical climate, variable lighting, and cultural sensitivities all influence how and what you can shoot. A well-chosen toolkit can make the difference between missed opportunities and memorable images. Start with lenses. A mid-range zoom, such as a 24-70mm, is ideal for the diverse environments you’ll encounter—from tight market stalls to expansive coastal views. It offers flexibility without the bulk of multiple prime lenses. A macro lens is also valuable for capturing fine details: the grain of carved wood, the texture of tapa cloth, or the intricate inlay of shell in a ceremonial bowl.

Weather protection is essential. Sudden downpours are common, especially in the afternoon. A simple rain cover for your camera can prevent costly damage. Spare batteries are another must—many art spaces are in areas with limited access to power, and high humidity can drain battery life faster than expected. A portable charger is a wise investment. Memory cards should be high-capacity and fast-writing, especially if you plan to shoot in RAW format for maximum post-processing flexibility.

Perhaps the most important part of your toolkit is not technical, but cultural. Always ask before photographing people, especially during cultural practices. A simple “May I take your photo?” accompanied by a smile goes a long way. If the answer is yes, take the time to engage. Share a few words, show genuine interest. Many artists appreciate the opportunity to explain their work. Consider offering to send them a print later—this builds trust and shows respect. For commercial use, such as publication or sale, written consent is necessary. Some art spaces have formal agreements; others rely on verbal understanding. When in doubt, err on the side of caution. The goal is not just to take pictures, but to build relationships.

Why This Matters: Photography as Cultural Bridge and Personal Awakening

Photographing the art spaces of Port Vila is more than a technical exercise. It is an act of witnessing. Each image captured is a small testament to a culture that thrives on resilience, creativity, and connection. In a world where traditional practices are often overshadowed by global trends, Port Vila stands as a quiet reminder that heritage can be both preserved and transformed. The artists here are not performing for outsiders. They are living their culture, shaping it with every stroke, every carve, every stitch.

For the photographer, this journey offers more than a portfolio of beautiful images. It offers a shift in perspective. It teaches patience—to wait for the right light, the right moment, the right permission. It teaches presence—to be fully in the space, to listen before shooting, to see beyond the surface. And it teaches humility—to recognize that every photograph is a collaboration, not a conquest. The camera does not take. It receives.

Ultimately, these images become bridges. They connect viewers to a way of life that values community, craftsmanship, and continuity. They invite others to look closely, to appreciate the depth behind the design, and to honor the hands that make it possible. In Port Vila, art is not something to be consumed. It is something to be felt, shared, and respected. And through the lens, we have the privilege to pass that feeling forward—not as tourists, but as witnesses, listeners, and keepers of light.